Friends: My predominant rice and bean diet of late hasn't been the best of fuel to keep me going. I had hoped some extra eating in Mwansa and a couple of moderate 50-mile days would revitalize me, but evidently my two hard days out of Biharamulo, partially on dirt, left me more drained than I realized, so I took a day of rest here in Bunda.

I've spent my day grazing on eggs and potatoes and chapati and bananas and baked sweet potatoes and more rice and beans. Pasta would have made my day, but I've only come across one restaurant in my two-and-a-half weeks here in East Africa serving it, and it was at a semi-Western restaurant in Uganda.

My day of leisure has allowed me to polish off the 664-page Lonely Planet guide to East Africa. I've read its every page, even those chapters on the Congo and Burundi and Rwanda and sections of Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania I won't be getting to, just to know what's out there and to get my money's worth out of the book.

Rwanda would have been quite interesting with its many genocide memorials. I would have been very curious to see how thoroughly I would have been searched at the border, as plastic bags have been banned in the country and are considered contraband. Much of my gear is separated by plastic bags in my four panniers. Lonely Planet didn't say, but Rwanda may be quite perilous for bicycling. The dogs there developed a taste for human flesh, feeding on the thousands of corpses laying about during the 1994 genocide that left over a million dead.

Like most of Lonely Planet's books, this was written by a team of writers. The lead author was a woman, perhaps explaining why the word "lovely" turned up more than just about any other adjective, over sixty times, more than twice as many as "spectacular," usually the most over-used descriptive word in guidebooks. These authors seemed to make a concerted effort to avoid "spectacular." More sites were "stunning" or "impressive" than were "spectacular," though not as many as were "amazing," "astounding," or "fantastic." Oddly enough there were as many "incredible" things to be seen as "spectacular," though no scale was offered to indicate what would be most mind-blowing--something labeled spectacular or incredible or amazing or stunning.

I am always attentive to what writers deem "ubiquitous" in a country. It is well-nigh impossible to write a travel book without finding items of ubiquity, as David Byrne proved in his recent "Bicycle Diaries" about his travels to cities around the world with his fold-up bicycle. He used "ubiquitous" nearly a dozen times, perhaps making up for being unable to use it in any of his songs.

The authors of this Lonely Planet guide used "ubiquitous" only seven times, about one-third as many as in the China book, though they couldn't find anything in Tanzania that was ubiquitous. In the Uganda section "takeaways" and "white and blue minibuses" and "Internet cafes" were ubiquitous in Kampala and "village walks" in a rural region. In Kenya "tuk-uks," "Smirnoff Ice" and "package holiday tat" were found to be ubiquitous.

As in all the Lonely Planet books there was a preponderance of Englishisms, such as "tat", some obvious and some not. Flashlights are generally referred to as "torches" but with "flashlight" in parentheses for its American readers. Cars have "boots" and can be rented from "hire agencies." One must be wary of "drink driving." Hotels have "plunge pools."

Lonely Planets used to be for extreme budget travelers. They are a fading breed. Formerly, the books regularly mentioned having a splurge, spending a few bucks more than normal on a meal or a hotel. Now the books rarely use the word splurge, and talk about $500 balloon trips and lodges that cost that much or more a night and other extravagances. Activities for children also would not have been part of their books and now are.

Still the books offer much useful information, such as the best shower in Uganda and the fastest computer. Though its writers are always tested to write with some flair and originality and avoid the formula, the formula isn't all that bad. I am glad to have plodded through the book and can now concentrate on more varied writing.

I'm hoping for an early start tomorrow and perhaps making it to Kenya.

Later, George

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Friday, February 26, 2010

Bunda, Tanzania

Friends: At every guest house I've stayed at in Tanzania I've had to fill out the same standard issue registration book requesting nationality, place of birth, where I've just come from, where I'm going next, occupation, tribe and a few others. Rather than leaving the tribe space blank, I identify myself as Apache, having shared an apartment the past ten years with someone who is part Apache.

It's not something that Debbie mentions very often or gives much evidence of, other than perhaps her affinity for gardening and sitting out in our recessed mini-courtyard reading and keeping a vigil on the neighborhood. I may exhibit more Apache tendencies than she does with my wanderings and longings to sleep out under the stars. So far no one has asked me about my tribe.

Among other things that is entered in the registration book is what one has paid for their room. That saved me one thousand shillings last night. I noticed everyone else had paid four thousand shillings while I had been charged five. When I pointed this out to the woman proprietor, she smiled sheepishly and gave me one thousand shillings back, about 75 cents, enough to pay for dinner.

The over-charging and gouging (the white tax) has been chronic the last couple of days since my ferry to Mwansa, leaving the isolated northwest of Tanzania, and venturing into a region frequented by Westerners. A street vendor quoted me the usual price of one thousand shillings for a two egg omelet then tried to get away with only giving me three thousand shillings change when I gave him a five thousand note, claiming it was one thousand shillings per egg. I laughed and said, "No, no." He had that extra one thousand ready to give me in case I protested, and he gave it to me with a smile. When he returned to his stand from the table I was sitting at, I could hear him laughingly tell his cronies that I knew better and hadn't fallen for his trick.

Another street vendor quoted me a price of one thousand shillings for a flour fritter that usually cost one hundred shillings. When I objected and said one hundred, she accepted it without protest. After dinner last night it took quite a bit of haggling to get 8500 shillings in change rather than the 7500 that the waitress tried to pass me. It helped that a nice English-speaking young man had joined me and assisted. He said she was just stupid and didn't have a computer for a mind, but I don't think she was stupid at all. Its getting quite tiresome having to be on guard for such things and continually having people trying to squeeze some extra shillings out of me.

Even the man I had dinner with, who was a small entrepreneur and had directed me to the lone guest house in the tiny village I was caught at when dark descended, had slight ulterior motives in befriending me. He came by the next morning to say goodbye and joined me for breakfast. I had just finished "I Dream of Africa," an excellent book by Kuki Gallman about moving to Kenya from Italy and living in a vast wilderness area with much wild life. She loses her teen-aged son to a snake bite and her husband to an automobile accident, but presses on. I was happy to pass the book on to this young man. He stuck it in the inside pocket of his sports coat. As we left the restaurant and headed to the main highway, someone called out to him. He very quickly and subtly opened up his jacket and pulled the book up just a smidgen to show his friend that yes, he had gotten something out of me.

As I was repairing my third flat tire of the trip along the road several hours later a schoolboy stopped and before saying anything politely asked, "Can you give me one thousand shillings?" Never have I felt so targeted. People treat me as if I am a human ATM machine freely dispensing to all and sundry. It makes me eager to escape this country and get back to the ultra-politeness of Uganda. Hardly anyone even chased me on their bike there. But first I must endure Kenya. At least the short section along Lake Victoria doesn't attract many Westerners.

This present stretch of Tanzania is along the Serengeti, which charges Westerners fifty dollars per day to enter. I got a good twenty-mile taste of the Serengeti without the fee. As I skirted its western border I could see herds of thousands of the wildebeests it is famous for along with hundreds of zebras and a few gazelles. At a one-lane wide bridge that traffic had to slow for, a handful of baboons were hanging out hoping for handouts.

Having had such a good taste of the abundant wild life gave me resolve to resist the offer of any safari company or tout in Bunda that might try to entice me to take a drive through the park. I cringed at the site of a couple of land-rovers filled with white-faces, knowing that I would have a headache if I were confined to such a vehicle, bouncing along the dirt roads of the park in search of wild life, especially after all the freedom I've been enjoying on the bike. It made me remember the claustrophobia and near nausea I felt a year ago when I took a bus for several hundred miles in South Africa to get to the Kalahari Desert for my ride through it.

Even though Bunda is at one of the entry points to the park, it is just another rough-and-tumble, slightly overgrown Tanzania village without a white to be seen or any tourist companies. Most tourists make their safari arrangements before arriving in the country, so I haven't been hounded here by tour operators looking for customers.

There are quite a few guest houses though in Bunda, all cheap, catering to locals. I am fortunate to have a shower tonight. Often I just have a five-gallon bucket of water and a small pail to pour the water over me. Last night I didn't even have that. Even though I was within a quarter mile of Lake Victoria, the guest house had no water pressure and no more water than enough to pour down the squat toilet. I refer to them as guest houses, as hotels in these East African countries are restaurants.

This is turning into a much more challenging trip than I imagined it would be, but one I am still happy to be doing.

Friend Robert offers this: "In the event your readers care to follow your journey, here is the link to that Lake Victoria map that I sent to you before you left. I have been following your travels, such as your recent ferry crossing, via this map."

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lake_Victoria_1968.jpg

Later. George

It's not something that Debbie mentions very often or gives much evidence of, other than perhaps her affinity for gardening and sitting out in our recessed mini-courtyard reading and keeping a vigil on the neighborhood. I may exhibit more Apache tendencies than she does with my wanderings and longings to sleep out under the stars. So far no one has asked me about my tribe.

Among other things that is entered in the registration book is what one has paid for their room. That saved me one thousand shillings last night. I noticed everyone else had paid four thousand shillings while I had been charged five. When I pointed this out to the woman proprietor, she smiled sheepishly and gave me one thousand shillings back, about 75 cents, enough to pay for dinner.

The over-charging and gouging (the white tax) has been chronic the last couple of days since my ferry to Mwansa, leaving the isolated northwest of Tanzania, and venturing into a region frequented by Westerners. A street vendor quoted me the usual price of one thousand shillings for a two egg omelet then tried to get away with only giving me three thousand shillings change when I gave him a five thousand note, claiming it was one thousand shillings per egg. I laughed and said, "No, no." He had that extra one thousand ready to give me in case I protested, and he gave it to me with a smile. When he returned to his stand from the table I was sitting at, I could hear him laughingly tell his cronies that I knew better and hadn't fallen for his trick.

Another street vendor quoted me a price of one thousand shillings for a flour fritter that usually cost one hundred shillings. When I objected and said one hundred, she accepted it without protest. After dinner last night it took quite a bit of haggling to get 8500 shillings in change rather than the 7500 that the waitress tried to pass me. It helped that a nice English-speaking young man had joined me and assisted. He said she was just stupid and didn't have a computer for a mind, but I don't think she was stupid at all. Its getting quite tiresome having to be on guard for such things and continually having people trying to squeeze some extra shillings out of me.

Even the man I had dinner with, who was a small entrepreneur and had directed me to the lone guest house in the tiny village I was caught at when dark descended, had slight ulterior motives in befriending me. He came by the next morning to say goodbye and joined me for breakfast. I had just finished "I Dream of Africa," an excellent book by Kuki Gallman about moving to Kenya from Italy and living in a vast wilderness area with much wild life. She loses her teen-aged son to a snake bite and her husband to an automobile accident, but presses on. I was happy to pass the book on to this young man. He stuck it in the inside pocket of his sports coat. As we left the restaurant and headed to the main highway, someone called out to him. He very quickly and subtly opened up his jacket and pulled the book up just a smidgen to show his friend that yes, he had gotten something out of me.

As I was repairing my third flat tire of the trip along the road several hours later a schoolboy stopped and before saying anything politely asked, "Can you give me one thousand shillings?" Never have I felt so targeted. People treat me as if I am a human ATM machine freely dispensing to all and sundry. It makes me eager to escape this country and get back to the ultra-politeness of Uganda. Hardly anyone even chased me on their bike there. But first I must endure Kenya. At least the short section along Lake Victoria doesn't attract many Westerners.

This present stretch of Tanzania is along the Serengeti, which charges Westerners fifty dollars per day to enter. I got a good twenty-mile taste of the Serengeti without the fee. As I skirted its western border I could see herds of thousands of the wildebeests it is famous for along with hundreds of zebras and a few gazelles. At a one-lane wide bridge that traffic had to slow for, a handful of baboons were hanging out hoping for handouts.

Having had such a good taste of the abundant wild life gave me resolve to resist the offer of any safari company or tout in Bunda that might try to entice me to take a drive through the park. I cringed at the site of a couple of land-rovers filled with white-faces, knowing that I would have a headache if I were confined to such a vehicle, bouncing along the dirt roads of the park in search of wild life, especially after all the freedom I've been enjoying on the bike. It made me remember the claustrophobia and near nausea I felt a year ago when I took a bus for several hundred miles in South Africa to get to the Kalahari Desert for my ride through it.

Even though Bunda is at one of the entry points to the park, it is just another rough-and-tumble, slightly overgrown Tanzania village without a white to be seen or any tourist companies. Most tourists make their safari arrangements before arriving in the country, so I haven't been hounded here by tour operators looking for customers.

There are quite a few guest houses though in Bunda, all cheap, catering to locals. I am fortunate to have a shower tonight. Often I just have a five-gallon bucket of water and a small pail to pour the water over me. Last night I didn't even have that. Even though I was within a quarter mile of Lake Victoria, the guest house had no water pressure and no more water than enough to pour down the squat toilet. I refer to them as guest houses, as hotels in these East African countries are restaurants.

This is turning into a much more challenging trip than I imagined it would be, but one I am still happy to be doing.

Friend Robert offers this: "In the event your readers care to follow your journey, here is the link to that Lake Victoria map that I sent to you before you left. I have been following your travels, such as your recent ferry crossing, via this map."

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lake_Victoria_1968.jpg

Later. George

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Mwansa, Tanzania

Friends: I could have taken a ferry across Lake Victoria from Bukoba to Mwansa, as Mbasa had encouraged me, and avoided the dirt road, but I had no regrets remaining faithful to my bicycle. But I couldn't avoid a ferry to cross a long, wide arm of the lake just before the large city of Mwansa.

I had the option of two ferries, one up near the shoreline of Lake Victoria, or a shorter ferry 15 miles or so down the arm. Taking the longer ferry would have cut ten miles from my ride, but it required twenty miles of riding on a rough dirt road. I wasn't entirely opposed to that, but just when I came to the junction with the dirt road the skies opened with a deluge, the third such I have experienced in the past week, turning the dirt road into a quagmire.

There is so little traffic crossing the inlet the ferries run only every two hours and only during day-light hours. Night driving is so discouraged in Tanzania, buses don't even run after dark. The 1500-mile bus ride from the capital city of Dar es Saleem to Mwansa, the country's second largest city, stops at dark giving the passengers the option of sleeping the night in the bus or slipping into a hotel.

I had no idea what the ferry schedule was. I luckily arrived just minutes before the second to last ferry for the day was due to depart. If I'd missed it, I wouldn't have been able to make it to Mwansa that night, 20 miles from the ferry. I could see the ferry loading up from a hill as I approached the lake. The final mile was on a rutted dirt road. That was a nervous last mile. I was the last one to board the ferry moments before it departed. It wasn't very big. Six trucks and four cars filled it. One truck and one car were left behind, waiting for the next ferry. I had been hoping to have at least a few minutes to spare so I could buy some food and eat during the half hour crossing, but I had to be satisfied with my last couple of bananas.

There was a white man gazing out over the side of the ferry, the first white I had seen since Sister Anna a few days ago. He wasn't dressed as a tourist in faux safari wear, nor in the sterile attire of a missionary, though he was a missionary of the economic sort, a representative of Caterpillar. He was an American who had been based in Johannesburg the past three-and-a-half years, traveling all over Africa selling and servicing equipment. He was a native of upstate New York, but had worked in Peoria, Illinois, the international headquarters of Caterpillar.

This was his first visit to Tanzania, and he had been impressed by how "tidy" and orderly it was compared to most of the places he had been in Africa. His only quibble was being charged $100 for his visa, when he had been told it was ordinarily $50. His Tanzanian contacts told him that what one is charged seemed to be up to the whim of the customs people at the time.

He was accustomed to such things in Africa, where bribery is an accepted part of doing business. It was most flagrant in Mozambique, he said. Mozambique borders South Africa to its northeast. I bicycled through it last winter and visited its once magnificent capital Maputo. I enjoyed my time in Mozambique very much. The Caterpillar man commented too on how impressive Maputo must have been back in its days of glory with wide boulevards and stately tall buildings before it gained independence from Portugal.

The Caterpillar man, whose name I never learned, though we did shake hands upon parting, had just come from the gold mine in Geita. He greatly enjoyed his job visiting such places and very much liked living in South Africa. I asked him how many times he had been robbed in South Africa. Not once he said, though just about everyone he knew had. He was very much looking forward to the World Cup. He said it had been good for his business and South Africa's economy. The country's infrastructure had been greatly improved. Highways and rail lines were being built all over and quite a few new stadiums were constructed as well, including one in Soweto, the black township outside of Johannesburg, where the championship match will be held. He had tickets for five of the matches.

The first six miles of the road beyond the ferry were dirt, though I was able to ride on a new road being constructed that was much smoother. I came to one section with a road crew working and was halted. I was told I couldn't continue and would have to divert to the old one-lane wide dirt road down a steep embankment. Just as I began attempting it, the Chinese foreman of the crew came over and waved me on. I made it into Mwansa just as dark settled in. It was a veritable city with several modern twenty-story tall glass semi-skyscrapers. There were stop lights and round-abouts and an array of Internet outlets, though still exasperatingly slow.

I've had to push it hard the past two days and am happy for some idle time. Its less than 200 miles to Kenya. I'll pass by the Serengeti on the way. Not even motorcyclists are allowed to ride through.

Thanks to Robert for posting a bunch more photos sent to me by George in Bukoba.

Later, George

I had the option of two ferries, one up near the shoreline of Lake Victoria, or a shorter ferry 15 miles or so down the arm. Taking the longer ferry would have cut ten miles from my ride, but it required twenty miles of riding on a rough dirt road. I wasn't entirely opposed to that, but just when I came to the junction with the dirt road the skies opened with a deluge, the third such I have experienced in the past week, turning the dirt road into a quagmire.

There is so little traffic crossing the inlet the ferries run only every two hours and only during day-light hours. Night driving is so discouraged in Tanzania, buses don't even run after dark. The 1500-mile bus ride from the capital city of Dar es Saleem to Mwansa, the country's second largest city, stops at dark giving the passengers the option of sleeping the night in the bus or slipping into a hotel.

I had no idea what the ferry schedule was. I luckily arrived just minutes before the second to last ferry for the day was due to depart. If I'd missed it, I wouldn't have been able to make it to Mwansa that night, 20 miles from the ferry. I could see the ferry loading up from a hill as I approached the lake. The final mile was on a rutted dirt road. That was a nervous last mile. I was the last one to board the ferry moments before it departed. It wasn't very big. Six trucks and four cars filled it. One truck and one car were left behind, waiting for the next ferry. I had been hoping to have at least a few minutes to spare so I could buy some food and eat during the half hour crossing, but I had to be satisfied with my last couple of bananas.

There was a white man gazing out over the side of the ferry, the first white I had seen since Sister Anna a few days ago. He wasn't dressed as a tourist in faux safari wear, nor in the sterile attire of a missionary, though he was a missionary of the economic sort, a representative of Caterpillar. He was an American who had been based in Johannesburg the past three-and-a-half years, traveling all over Africa selling and servicing equipment. He was a native of upstate New York, but had worked in Peoria, Illinois, the international headquarters of Caterpillar.

This was his first visit to Tanzania, and he had been impressed by how "tidy" and orderly it was compared to most of the places he had been in Africa. His only quibble was being charged $100 for his visa, when he had been told it was ordinarily $50. His Tanzanian contacts told him that what one is charged seemed to be up to the whim of the customs people at the time.

He was accustomed to such things in Africa, where bribery is an accepted part of doing business. It was most flagrant in Mozambique, he said. Mozambique borders South Africa to its northeast. I bicycled through it last winter and visited its once magnificent capital Maputo. I enjoyed my time in Mozambique very much. The Caterpillar man commented too on how impressive Maputo must have been back in its days of glory with wide boulevards and stately tall buildings before it gained independence from Portugal.

The Caterpillar man, whose name I never learned, though we did shake hands upon parting, had just come from the gold mine in Geita. He greatly enjoyed his job visiting such places and very much liked living in South Africa. I asked him how many times he had been robbed in South Africa. Not once he said, though just about everyone he knew had. He was very much looking forward to the World Cup. He said it had been good for his business and South Africa's economy. The country's infrastructure had been greatly improved. Highways and rail lines were being built all over and quite a few new stadiums were constructed as well, including one in Soweto, the black township outside of Johannesburg, where the championship match will be held. He had tickets for five of the matches.

The first six miles of the road beyond the ferry were dirt, though I was able to ride on a new road being constructed that was much smoother. I came to one section with a road crew working and was halted. I was told I couldn't continue and would have to divert to the old one-lane wide dirt road down a steep embankment. Just as I began attempting it, the Chinese foreman of the crew came over and waved me on. I made it into Mwansa just as dark settled in. It was a veritable city with several modern twenty-story tall glass semi-skyscrapers. There were stop lights and round-abouts and an array of Internet outlets, though still exasperatingly slow.

I've had to push it hard the past two days and am happy for some idle time. Its less than 200 miles to Kenya. I'll pass by the Serengeti on the way. Not even motorcyclists are allowed to ride through.

Thanks to Robert for posting a bunch more photos sent to me by George in Bukoba.

Later, George

More Tanzania photos

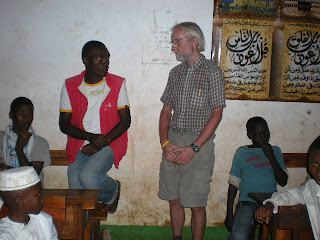

George, the young man responsible for providing these photos, with a group of HIV orphans and albino children

Fisherman unloading the day's catch behind me.

Mbasa and I outside the home of the 14-year old HIV orphan where she lives with her daughter and grandparents and brother and sister.

Taking a question from one of the orphans

Goat stew being served onto communal platter

Flanked by Mbasa and Mr. Raza before lunch on the floor where we ate

Stirring the goat stew along side the cook.

Mbasa and I in the room where I spoke to the orphans.

Geita, Tanzania

Friends: I don't know if I've inspired any of the many, many local cyclists I've encountered to ride their bike around Lake Victoria, as I'm doing, or even to go for a ride beyond the next village, but I have inspired quite a few to ride a bit harder or to continue biking up the long hills they ordinarily walk up. I regularly whiz past walking or leisurely-pedaling cyclists, and then moments later hear their grinding bikes fast closing in on me, then tagging along or even sprinting past.

Rarely is it more than one or two at a time, but yesterday, in the late afternoon, I was a veritable Pied Piper of cyclists with an ever-evolving posse of seven or eight swarming along with me for a good half hour or more. After one sped up to join me we accumulated more, one by one, as we overtook another or others slipped onto the road from the fields where they had been working. We shed some when we reached their destination but soon were joined by another.

We were a symphonic cacophony of rickety bicycles with rattling fenders and kick stands and unoiled chains and clanking tools, as just about every bike had a tool of some sort, machete or shovel or hoe, lashed to its rack. But no loose or mal-functioning derailleurs added to the clatter, as these were all heavy-duty one-speeds. I never overtly try to outrace a cyclist when he latches on to me, not wishing to unnecessarily expend energy, but I am often tempted to stop and oil someone's chain that is getting on my nerves. If I had made oiling chains the mission of this trip, I would have dispensed several gallons of lubricant already.

Most of the guys in this group hung back behind me, but occasionally some one would feel frisky enough to show-boat and spurt on ahead, often just before he reached his turn-off. I am always inclined to do some drafting, but my nostrils would not stand for it here. These young men were all in desperate need of a shower after a hard day in the fields. Their ragged clothes were saturated with dirt, and may not have been washed for weeks. I'm not sure who'd had the harder day, they laboring in the fields or me laboring on my bike since before seven a.m. and having come over sixty miles, much of it on dirt.

If I could have taken a photo of my accompanying gang of desperadoes, those seeing this ragtag band of ruffians would be alarmed, fearing for my safety. Were they my captors or my protectors? Our cultures, our backgrounds, our dreams could not be more different, but we were united by the bike and sharing in a gallant, carefree romp.

Having once been attacked in Africa along the road by a pair of guys who looked no different than many of those beside me, I couldn't help but think of that incident and feel at least a pinprick of concern, knowing that I'd be completely at their mercy if they chose to close in on me. There was very little traffic and we came upon many an isolated bend with no one else about. But if I gave much weight to such concerns I'd be back in Chicago stuck in some sedentary job, fearful of even messengering.

Whatever wariness I may have felt that they might be hatching a plot was continually short-circuited by the lively and animated Swahilian chatter laced with unmistakable levity and good cheer that was nearly loud enough to drown out the clatter of their bikes. Their non-stop banter was periodically broken by a shout of delight to those we passed along the road, also reassuring me that they were just having a rollicking grand time riding along with this crazy white man. I knew they most certainly had to be wondering what untold treasures resided in my panniers and what it would be like to ride such a thorough-bred of a bicycle as I was riding, but the occasional smiles we exchanged allayed whatever concerns I might have had about them having any untoward designs.

People frequently comment how poor they are and what a poor country they live in. Isoufou, the kindly, gentle-mannered 20-year old who befriended me in Biharamulo, was far from poor by local standards, though he said he felt as if he was mired in poverty. His parents ran a thriving restaurant that was always packed. He had a cell phone and wore nice clothes. His English was very good, much better than I initially realized, before he overcame his timidity and truly opened up. We shared a couple meals together and he showed me around his village. He stopped by my hotel a couple times to check in on me and came by my last night to say farewell, hoping we could stay in touch. Like many, he would love to come to America. As he rose to say goodbye, out of nowhere, he blurted out, as if it took all his courage, "Could you give me 10,000 shillings (about $8)?"

I told him I really didn't have any shillings to spare, partially not wishing to encourage such behavior. I have the impression that everyone assumes I have more money than I know what to do with and would happily give them some if they asked for it.

Still, I encounter many acts of generosity, though nothing on the level of China. The government office that allowed me to use their computer for two hours in Biharamulo did not ask for any money. Nor did Mr. Rasa or his cohorts ask for a donation to their charity, though they hope I will in the future.

I am presently closing in on Mwansa, the largest city on Lake Victoria and close to the half-way point around the lake. I feared I would have dirt road all the way to Geita, but the dirt gave way to pavement 47 miles out of Bhiaramulo. After two days of dirt, it was a glorious moment to regain pavement.

I was able to polish off the final 40 paved miles to Geita just before dark. There were quite a few small guest houses to choose from as Geita is a thriving gold-mining town. Tanzania is the third leading gold-producer in Africa behind South Africa and Ghana. Tanzania's largest gold mine is just outside of Geita.

I had to pass up miles and miles of first-rate forest camping as I didn't have enough water to get me through the night. It was another hard hard day on the bike. I was dying to pour a bottle of water over my head, but I had none to spare. I put in nearly nine hours in the saddle in less than twelve hours of light, to complete those 87 miles. I was rewarded with an ice-cold liter-and-a-half bottle of Dasani water, my best and coldest drink these past two weeks. After I polished it off I returned later for another, but that was the only one the small shop owner had. Its always nice to have the flavor of a soft drink, but cold water is the most refreshing drink I can have, and what my body truly craves.

Later, George

Rarely is it more than one or two at a time, but yesterday, in the late afternoon, I was a veritable Pied Piper of cyclists with an ever-evolving posse of seven or eight swarming along with me for a good half hour or more. After one sped up to join me we accumulated more, one by one, as we overtook another or others slipped onto the road from the fields where they had been working. We shed some when we reached their destination but soon were joined by another.

We were a symphonic cacophony of rickety bicycles with rattling fenders and kick stands and unoiled chains and clanking tools, as just about every bike had a tool of some sort, machete or shovel or hoe, lashed to its rack. But no loose or mal-functioning derailleurs added to the clatter, as these were all heavy-duty one-speeds. I never overtly try to outrace a cyclist when he latches on to me, not wishing to unnecessarily expend energy, but I am often tempted to stop and oil someone's chain that is getting on my nerves. If I had made oiling chains the mission of this trip, I would have dispensed several gallons of lubricant already.

Most of the guys in this group hung back behind me, but occasionally some one would feel frisky enough to show-boat and spurt on ahead, often just before he reached his turn-off. I am always inclined to do some drafting, but my nostrils would not stand for it here. These young men were all in desperate need of a shower after a hard day in the fields. Their ragged clothes were saturated with dirt, and may not have been washed for weeks. I'm not sure who'd had the harder day, they laboring in the fields or me laboring on my bike since before seven a.m. and having come over sixty miles, much of it on dirt.

If I could have taken a photo of my accompanying gang of desperadoes, those seeing this ragtag band of ruffians would be alarmed, fearing for my safety. Were they my captors or my protectors? Our cultures, our backgrounds, our dreams could not be more different, but we were united by the bike and sharing in a gallant, carefree romp.

Having once been attacked in Africa along the road by a pair of guys who looked no different than many of those beside me, I couldn't help but think of that incident and feel at least a pinprick of concern, knowing that I'd be completely at their mercy if they chose to close in on me. There was very little traffic and we came upon many an isolated bend with no one else about. But if I gave much weight to such concerns I'd be back in Chicago stuck in some sedentary job, fearful of even messengering.

Whatever wariness I may have felt that they might be hatching a plot was continually short-circuited by the lively and animated Swahilian chatter laced with unmistakable levity and good cheer that was nearly loud enough to drown out the clatter of their bikes. Their non-stop banter was periodically broken by a shout of delight to those we passed along the road, also reassuring me that they were just having a rollicking grand time riding along with this crazy white man. I knew they most certainly had to be wondering what untold treasures resided in my panniers and what it would be like to ride such a thorough-bred of a bicycle as I was riding, but the occasional smiles we exchanged allayed whatever concerns I might have had about them having any untoward designs.

People frequently comment how poor they are and what a poor country they live in. Isoufou, the kindly, gentle-mannered 20-year old who befriended me in Biharamulo, was far from poor by local standards, though he said he felt as if he was mired in poverty. His parents ran a thriving restaurant that was always packed. He had a cell phone and wore nice clothes. His English was very good, much better than I initially realized, before he overcame his timidity and truly opened up. We shared a couple meals together and he showed me around his village. He stopped by my hotel a couple times to check in on me and came by my last night to say farewell, hoping we could stay in touch. Like many, he would love to come to America. As he rose to say goodbye, out of nowhere, he blurted out, as if it took all his courage, "Could you give me 10,000 shillings (about $8)?"

I told him I really didn't have any shillings to spare, partially not wishing to encourage such behavior. I have the impression that everyone assumes I have more money than I know what to do with and would happily give them some if they asked for it.

Still, I encounter many acts of generosity, though nothing on the level of China. The government office that allowed me to use their computer for two hours in Biharamulo did not ask for any money. Nor did Mr. Rasa or his cohorts ask for a donation to their charity, though they hope I will in the future.

I am presently closing in on Mwansa, the largest city on Lake Victoria and close to the half-way point around the lake. I feared I would have dirt road all the way to Geita, but the dirt gave way to pavement 47 miles out of Bhiaramulo. After two days of dirt, it was a glorious moment to regain pavement.

I was able to polish off the final 40 paved miles to Geita just before dark. There were quite a few small guest houses to choose from as Geita is a thriving gold-mining town. Tanzania is the third leading gold-producer in Africa behind South Africa and Ghana. Tanzania's largest gold mine is just outside of Geita.

I had to pass up miles and miles of first-rate forest camping as I didn't have enough water to get me through the night. It was another hard hard day on the bike. I was dying to pour a bottle of water over my head, but I had none to spare. I put in nearly nine hours in the saddle in less than twelve hours of light, to complete those 87 miles. I was rewarded with an ice-cold liter-and-a-half bottle of Dasani water, my best and coldest drink these past two weeks. After I polished it off I returned later for another, but that was the only one the small shop owner had. Its always nice to have the flavor of a soft drink, but cold water is the most refreshing drink I can have, and what my body truly craves.

Later, George

Monday, February 22, 2010

Biharamulo, Tanzania

Friends: A several hour hard rain last night has left me stranded in the middle of a 160-mile stretch of dirt road that has been turned into a river of mud. Luckily I spent the night in a hotel in the town of Biharamulo. If I had camped last night, I could well be stuck out in who knows where.

This stretch of unpaved road came as a complete surprise. Everyone I asked in Bukoba told me the road was fine all around the lake through Tanzania. My map did not indicate any lesser of a road after Bukoba than the paved road I'd been on. Nor did an American nun, who had spent the past ten years in a town 15 miles south of Bukoba, warn me of the unpaved road ahead. She only told me that the road was greatly improved from when she first came to Tanzania. At that time it was a rough dirt track through the jungle that wasn't very safe. Bandits would fall a tree across the road and rob buses. That no longer was a worry, she said.

I stopped off to see Sister Anna at the recommendation of Mr. Raza in Bukoba. He said she was a very interesting lady who was doing excellent work. She was a Franciscan nun who set up this mission ten years ago after doing similar work in Cambodia and Haiti and elsewhere. She had last been posted in Springfield, Illinois, the national headquarters for the Franciscan nuns. She was an older, most vibrant lady, who still retained a hint of a Brooklyn accent. She was a genuine self-less humanitarian, who had devoted her life to helping others. As isolated as she was, she still managed to keep up with worldly events. Tiger Woods had made his public apology the day before. She was well aware of his travails and felt compassion for him, commenting that everyone has their faults and that no one should throw stones.

We spent an hour or so chatting in the vestibule to her quarters that housed three other nuns, all from India. Before I left, she filled my water bottles and gave me an extra liter-and-a-half and also a handful of Kellogg breakfast bars and bananas. It was an hour very well spent with a most extraordinary person.

It was 30 miles before the pavement gave out as I approached the town of Mulega, big enough to have a few guest houses. It was an hour before dark. I could have stayed there, but there had been many patches of forest, some of them recently planted. All day I had been looking forward to a quiet night in my tent in my own private little forest. But the dirt road continued beyond Mulega and turned steeply hilly, greatly slowing my speed and limiting my range. I had to scratch out an encampment among some bushes all too close to a few homes. I could hear people talking in the evening, though none wandered through the surrounding bush protecting me.

I was very glad the next morning that I had pushed on an extra five miles, as the going continued very slow and every mile closer to pavement was precious. It took me two hours to go eleven miles to the next village where I could get some food and drink. It was already turning hot. I have had occasional cloudy days that made a considerable difference in my comfort-level. I couldn't count on such conditions today. I had three strong strikes against me--the rough road, the rugged, hilly terrain and the lack of clouds.

I debated if I could have one wish to make my day easier would I want the terrain to level or the road to turn to pavement or some cloud cover. I wished for the terrain to level, as that would require considerable less effort, keeping me from over-heating, and also knowing that when the road leveled it was generally less rough. Four miles later my wish was miraculously granted when the road turned inland a bit away from the lake. Within an hour I had upped my average speed from less than six miles per hour to over 7.5 miles per hour for the day. I would soon have it up to eight miles per hour and then nine. It began to look possible that I could reach Biharamulo before dark. I didn't care to wild camp two nights in a row, longing for a shower and a substantial meal after another hard, hot, dusty day. But I could only guess how far it was to Biharmulo. I hoped it was no more than 70 miles.

It was another 20 miles before I came to the next village. Two shacks sold soft drinks, but no food other than oranges, mangoes and bananas. Just after that town I entered a national park. The road was just one-lane wide and not well maintained. My speed dropped. It was a Sunday, so there was hardly any traffic, about half an hour between passing vehicles. Near human-sized primates chattered in the trees and made occasional dashes across the road.

It was over three hours of non-stop riding until I came to another village of a small cluster of huts. I was really pushing myself to reach pavement and civilization. There didn't seem to be a store amongst them. I asked some men "Soda?" and they pointed at a building with a side window. The young boy at the window shook his head at my query of "Sodas." Looking in I could see an empty case on the floor.

He pointed at another hut across the way. It had a few bottles of soda and bottled water on a shelf, but no refrigerator. I opted for a bottle of pineapple Fanta, drinking it sitting in the shade of a tree, sharing it with a woman drinking a similar bottle. A couple dozen children and a few teen-aged boys ventured over and sat in front of me. After a few minutes a young man offered me a tube of biscuits. I wasn't sure if he was selling them or if it was a gift. He gestured towards my handlebar bag, indicating it was a gift, the first such offering I've had on this trip, and from perhaps the poorest people I've encountered.

After slowly sipping and savoring the soda, I bought a bottle of water. While I was up I retrieved my camera from my bike. After a few swigs of water, I pointed it towards the children without fully raising it to my eye. They quickly scattered, bringing laughter from the older folk. After I put the camera down, they crept back. A few minutes later, I tried again, but they once again fled. On my third attempt, a few bravely stood their ground. After I snapped a picture and nothing happened, the others returned and implied they wanted their picture taken too, some even flexing their muscles and clownishly posing.

I was down to two hours of daylight and still didn't know how much further it was to Biharamulo. About five miles later I came upon a stranded truck in the road with two men working on it. They greeted me in English. I stopped, hoping they spoke more than just a few words. They did, and they could tell me I was within five kilometers of Biharamulo. I was saved. I could have a shower and a good feed.

Birharmulo had several guest houses to choose from, but it was still not much of a town, no real center, just a network of rough dirt roads. I didn't notice any restaurants. When I asked a guy at a small hut that I bought water from if there was a restaurant nearby, a friend said he would take me. It was off on a side road. I never would have recognized it as a restaurant, though it was a thriving place. The 20-year old son of the owner spoke some English, but not as much as a 25-year old English teacher who soon joined us. This town was truly off the beaten track, even though it was on the road that circuited Lake Victoria. None could ever remember a Westerner stopping there.

It was nearly dark after I had finished my dinner of rice and beans and two hunks of beef. The two English-speakers accompanied me to the guest house next door. There was just one self-contained room with a squat toilet, but without any running water, just a bucket. I had been dreaming about a shower all day, but any water would do. I had bathed similarly at Bukoba two nights before. My benefactors said they would like to give me a walk around town after I had bathed. I told them I was very, very tired, and I truly was, but that maybe I had strength for a 15 or 20 minute stroll.

It was pitch dark with no street lights in the town when I returned to the restaurant. We decided to just have a cup of hot milk and chat some more. They were all looking forward to the World Cup soccer tournament this June, taking place in Africa for the first time. Like everyone I have asked about it, they will be rooting for Brazil, and watching as much of it as they could. There were already signs outside of bars in the town saying that the World Cup would be shown there, even though its nearly three months away.

I was told there was an Internet cafe here, but when I went in search of it, I was told it was not working, but the local government office would let me use their computer, where I am now.

Later, George

This stretch of unpaved road came as a complete surprise. Everyone I asked in Bukoba told me the road was fine all around the lake through Tanzania. My map did not indicate any lesser of a road after Bukoba than the paved road I'd been on. Nor did an American nun, who had spent the past ten years in a town 15 miles south of Bukoba, warn me of the unpaved road ahead. She only told me that the road was greatly improved from when she first came to Tanzania. At that time it was a rough dirt track through the jungle that wasn't very safe. Bandits would fall a tree across the road and rob buses. That no longer was a worry, she said.

I stopped off to see Sister Anna at the recommendation of Mr. Raza in Bukoba. He said she was a very interesting lady who was doing excellent work. She was a Franciscan nun who set up this mission ten years ago after doing similar work in Cambodia and Haiti and elsewhere. She had last been posted in Springfield, Illinois, the national headquarters for the Franciscan nuns. She was an older, most vibrant lady, who still retained a hint of a Brooklyn accent. She was a genuine self-less humanitarian, who had devoted her life to helping others. As isolated as she was, she still managed to keep up with worldly events. Tiger Woods had made his public apology the day before. She was well aware of his travails and felt compassion for him, commenting that everyone has their faults and that no one should throw stones.

We spent an hour or so chatting in the vestibule to her quarters that housed three other nuns, all from India. Before I left, she filled my water bottles and gave me an extra liter-and-a-half and also a handful of Kellogg breakfast bars and bananas. It was an hour very well spent with a most extraordinary person.

It was 30 miles before the pavement gave out as I approached the town of Mulega, big enough to have a few guest houses. It was an hour before dark. I could have stayed there, but there had been many patches of forest, some of them recently planted. All day I had been looking forward to a quiet night in my tent in my own private little forest. But the dirt road continued beyond Mulega and turned steeply hilly, greatly slowing my speed and limiting my range. I had to scratch out an encampment among some bushes all too close to a few homes. I could hear people talking in the evening, though none wandered through the surrounding bush protecting me.

I was very glad the next morning that I had pushed on an extra five miles, as the going continued very slow and every mile closer to pavement was precious. It took me two hours to go eleven miles to the next village where I could get some food and drink. It was already turning hot. I have had occasional cloudy days that made a considerable difference in my comfort-level. I couldn't count on such conditions today. I had three strong strikes against me--the rough road, the rugged, hilly terrain and the lack of clouds.

I debated if I could have one wish to make my day easier would I want the terrain to level or the road to turn to pavement or some cloud cover. I wished for the terrain to level, as that would require considerable less effort, keeping me from over-heating, and also knowing that when the road leveled it was generally less rough. Four miles later my wish was miraculously granted when the road turned inland a bit away from the lake. Within an hour I had upped my average speed from less than six miles per hour to over 7.5 miles per hour for the day. I would soon have it up to eight miles per hour and then nine. It began to look possible that I could reach Biharamulo before dark. I didn't care to wild camp two nights in a row, longing for a shower and a substantial meal after another hard, hot, dusty day. But I could only guess how far it was to Biharmulo. I hoped it was no more than 70 miles.

It was another 20 miles before I came to the next village. Two shacks sold soft drinks, but no food other than oranges, mangoes and bananas. Just after that town I entered a national park. The road was just one-lane wide and not well maintained. My speed dropped. It was a Sunday, so there was hardly any traffic, about half an hour between passing vehicles. Near human-sized primates chattered in the trees and made occasional dashes across the road.

It was over three hours of non-stop riding until I came to another village of a small cluster of huts. I was really pushing myself to reach pavement and civilization. There didn't seem to be a store amongst them. I asked some men "Soda?" and they pointed at a building with a side window. The young boy at the window shook his head at my query of "Sodas." Looking in I could see an empty case on the floor.

He pointed at another hut across the way. It had a few bottles of soda and bottled water on a shelf, but no refrigerator. I opted for a bottle of pineapple Fanta, drinking it sitting in the shade of a tree, sharing it with a woman drinking a similar bottle. A couple dozen children and a few teen-aged boys ventured over and sat in front of me. After a few minutes a young man offered me a tube of biscuits. I wasn't sure if he was selling them or if it was a gift. He gestured towards my handlebar bag, indicating it was a gift, the first such offering I've had on this trip, and from perhaps the poorest people I've encountered.

After slowly sipping and savoring the soda, I bought a bottle of water. While I was up I retrieved my camera from my bike. After a few swigs of water, I pointed it towards the children without fully raising it to my eye. They quickly scattered, bringing laughter from the older folk. After I put the camera down, they crept back. A few minutes later, I tried again, but they once again fled. On my third attempt, a few bravely stood their ground. After I snapped a picture and nothing happened, the others returned and implied they wanted their picture taken too, some even flexing their muscles and clownishly posing.

I was down to two hours of daylight and still didn't know how much further it was to Biharamulo. About five miles later I came upon a stranded truck in the road with two men working on it. They greeted me in English. I stopped, hoping they spoke more than just a few words. They did, and they could tell me I was within five kilometers of Biharamulo. I was saved. I could have a shower and a good feed.

Birharmulo had several guest houses to choose from, but it was still not much of a town, no real center, just a network of rough dirt roads. I didn't notice any restaurants. When I asked a guy at a small hut that I bought water from if there was a restaurant nearby, a friend said he would take me. It was off on a side road. I never would have recognized it as a restaurant, though it was a thriving place. The 20-year old son of the owner spoke some English, but not as much as a 25-year old English teacher who soon joined us. This town was truly off the beaten track, even though it was on the road that circuited Lake Victoria. None could ever remember a Westerner stopping there.

It was nearly dark after I had finished my dinner of rice and beans and two hunks of beef. The two English-speakers accompanied me to the guest house next door. There was just one self-contained room with a squat toilet, but without any running water, just a bucket. I had been dreaming about a shower all day, but any water would do. I had bathed similarly at Bukoba two nights before. My benefactors said they would like to give me a walk around town after I had bathed. I told them I was very, very tired, and I truly was, but that maybe I had strength for a 15 or 20 minute stroll.

It was pitch dark with no street lights in the town when I returned to the restaurant. We decided to just have a cup of hot milk and chat some more. They were all looking forward to the World Cup soccer tournament this June, taking place in Africa for the first time. Like everyone I have asked about it, they will be rooting for Brazil, and watching as much of it as they could. There were already signs outside of bars in the town saying that the World Cup would be shown there, even though its nearly three months away.

I was told there was an Internet cafe here, but when I went in search of it, I was told it was not working, but the local government office would let me use their computer, where I am now.

Later, George

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Tanzania photos

Friday, February 19, 2010

A Day in Bukoba

Friends: My Friday arrival in Bukoba happened to be the day of a weekly lunch for 60 HIV orphans hosted by the owner of the petrol station that Mbasa manages. The boss, Mr. Raza, invited me to the luncheon and asked if I would give a talk to the orphans about my travels. He said it was the best meal many of the orphans ate all week. It would be a feast of two goats. He promised that I would be amazed by the amount of food the kids would eat.

Looking after the orphans was just one of several of Mr. Raza's humanitarian efforts. He runs his own NGO (Izaas Medical Project) trying to find limbs for amputees, many of whom are albino children who have had an arm or leg severed by a witch doctor who believes the limb can cure some ailment. Mr. Raza has enlisted the aid of several American and Dutch doctors, who pay periodic visits to Bukoba. He also has on staff a local doctor who provides free medical service every morning.

Mr. Raza is a Muslim of Indian heritage, born here in Bukoba. As he passionately described his many endeavors he said, "Now you can tell your Mr. Bush that not all Muslims are terrorists. The maiming and carnage he has caused is just terrible. You Americans only get your news from CNN. You are not learning the truth. You need to listen to the Arabic Al Jeezera news to know what is really going on in Iraq and Afghanistan."

Mr. Raza preceded me to the luncheon to join the orphans in prayer with a Muslim minister. Mbasa escorted me to the facility 45 minutes later. When I arrived a young man, also by the name of George, awaited me with a digital camera to photograph my appearance. He was from Dar es Salem, the capital of Tanzania nearly 1,000 miles away. He was three-weeks into a three-month assignment helping Mr. Raza with his computer work and fund raising. He was exceptionally bright and hospitable, a fine young man, who became my escort for the remainder of my time in Bukoba.

He said he would not be joining us for the meal as he was fasting during daylight hours for Lent, which had begun three days ago. He, like Mbasa, is an ardent Catholic. The orphans were still in prayer when we arrived. In the courtyard was a huge pot full of rice and a second huge pot of goat stew simmering over a fire. I helped stirring the stew with an oar. Before lunch I was introduced to the orphans by Mr. Raza. The orphans all sat on the floor, girls to one side and boys to the other.

After he talked about me for several minutes a dozen trays were brought out with the goat stew atop a mound of rice and placed among the students. Mbasa and I and the Islamic minister had our own tray. We too sat on the floor to eat. No utensils were provided. We ate the stew by balling it up with a handful of rice. The students about us devoured their platters well before we did. We had way more than we could eat. When we offered it to a group of boys nearby they quickly polished it off. All the while, George hovered about taking photos.

We adjourned to a second room for my talk. It was mostly a question and answer session translated by George. A few of the students spoke English but were too bashful to speak loudly and asked me to come near them so they could speak to me directly. The first question was, "Do you think Tanzania is a poor country?" I said I had only been in the country one day and that I was very impressed by the quality of its roads and the buildings I had seen and the stores selling many things. Someone else wanted me to compare my bike to Tanzanian bikes. I was also asked if I was afraid of animals camping out at night. I said, I thought the animals were more afraid of me than I of them. Towards the end someone asked me to ride my bike for them. I demonstrated my clip-in pedals. That grabbed their attention, drawing them out of their seats for a closer look.

After the session Mbasa and George took me to the one-room, dirt-walled shack where one of the orphans, an unwed 14-year old girl with a baby, lived with her grand-parents and brother and sister. They encouraged me to take pictures and invited me to hold the baby. They kept telling me how horrible her circumstances were, pointing out the corner of the unlit hovel that was her bed. I didn't tell them that I spent several winters living in a dirt-floored hut one-third the size of this house in Mexico with a girl friend.

I had planned to put up my tent at a lakeside campgrounds, but George invited me to spend the night in his compound, where one of the orphans lived and was looked after by an amputee. In the courtyard were two goats tied up munching hay. George said they had just arrived and would be next Friday's luncheon.

I had yet to see Bukoba's Lake Victoria shoreline, about a half mile away. It was late in the afternoon, so I made a quick ride down to the lake and then rejoined George and Mbasa and Mr. Raza at the petrol station. Mr. Raza gave me a letter to deliver to an American nun who lived at a convent 20 miles south on my route the next day. We shared a glass of freshly squeezed sugar cane juice, then George and I walked back to his quarters where the caretaker prepared dinner for us. While we waited George gave me a photo show on his computer of the many people Mr. Raza had assisted, with close-ups of many of their horrific ailments.

His screen saver was a photo of Stonehenge. George didn't know what it was, he just liked the image. He thought it was a natural wonder and was shocked to learn that it had been created by pre-historic man. I explained that it served as a calendar. It was also news to George that at the extremes in the northern and southern hemispheres in the summer time it is daylight until midnight or later and that in the winter time it is dark for most of the day. On George's second lap top his screen saver was the rapper 50 Cents, but the music he chose to play was by Abba, a group he likes even more.

It was nearly ten o'clock when we were through with dinner. We took a stroll through the mostly quiet down town in search of an open store so George could buy some cigarettes. Rather than a pack, he bought four. George had a bunk in his room, but I chose to set up my tent on the concrete of the courtyard. The goats were put into a room for the night.

The next morning Mbasa came by to take me to the lakeside to see the fish market. George came along with his camera. I rode my bike while Mbasa rode on the back of a motorcycle and George on the back of a bicycle. There were clusters of bicyclists all over town offering rides on their rear racks. Short rides were 200 shillings, with 1300 to the dollar. Mbasa was well known among the fishermen. The day before when I asked a fisherman if I could take his picture he wanted 1000 shillings. Today no one made any such demands. Dots of islands lay off the shore, some large enough for people to live on. Mbasa bought a couple of the Nile Perch for his luncheon.

When we said our farewells I thanked them for their great hospitality and tremendous welcome to Tanzania. Mbasa assured me I would be treated well during my entire stay. Unlike many of its neighboring countries that have been riven by tribal rivalries that has resulted in great bloodshed, Tanzania has been most peaceable. "We Tanzanians like each other," Mbasa said.

Later, George

Looking after the orphans was just one of several of Mr. Raza's humanitarian efforts. He runs his own NGO (Izaas Medical Project) trying to find limbs for amputees, many of whom are albino children who have had an arm or leg severed by a witch doctor who believes the limb can cure some ailment. Mr. Raza has enlisted the aid of several American and Dutch doctors, who pay periodic visits to Bukoba. He also has on staff a local doctor who provides free medical service every morning.

Mr. Raza is a Muslim of Indian heritage, born here in Bukoba. As he passionately described his many endeavors he said, "Now you can tell your Mr. Bush that not all Muslims are terrorists. The maiming and carnage he has caused is just terrible. You Americans only get your news from CNN. You are not learning the truth. You need to listen to the Arabic Al Jeezera news to know what is really going on in Iraq and Afghanistan."

Mr. Raza preceded me to the luncheon to join the orphans in prayer with a Muslim minister. Mbasa escorted me to the facility 45 minutes later. When I arrived a young man, also by the name of George, awaited me with a digital camera to photograph my appearance. He was from Dar es Salem, the capital of Tanzania nearly 1,000 miles away. He was three-weeks into a three-month assignment helping Mr. Raza with his computer work and fund raising. He was exceptionally bright and hospitable, a fine young man, who became my escort for the remainder of my time in Bukoba.

He said he would not be joining us for the meal as he was fasting during daylight hours for Lent, which had begun three days ago. He, like Mbasa, is an ardent Catholic. The orphans were still in prayer when we arrived. In the courtyard was a huge pot full of rice and a second huge pot of goat stew simmering over a fire. I helped stirring the stew with an oar. Before lunch I was introduced to the orphans by Mr. Raza. The orphans all sat on the floor, girls to one side and boys to the other.

After he talked about me for several minutes a dozen trays were brought out with the goat stew atop a mound of rice and placed among the students. Mbasa and I and the Islamic minister had our own tray. We too sat on the floor to eat. No utensils were provided. We ate the stew by balling it up with a handful of rice. The students about us devoured their platters well before we did. We had way more than we could eat. When we offered it to a group of boys nearby they quickly polished it off. All the while, George hovered about taking photos.

We adjourned to a second room for my talk. It was mostly a question and answer session translated by George. A few of the students spoke English but were too bashful to speak loudly and asked me to come near them so they could speak to me directly. The first question was, "Do you think Tanzania is a poor country?" I said I had only been in the country one day and that I was very impressed by the quality of its roads and the buildings I had seen and the stores selling many things. Someone else wanted me to compare my bike to Tanzanian bikes. I was also asked if I was afraid of animals camping out at night. I said, I thought the animals were more afraid of me than I of them. Towards the end someone asked me to ride my bike for them. I demonstrated my clip-in pedals. That grabbed their attention, drawing them out of their seats for a closer look.

After the session Mbasa and George took me to the one-room, dirt-walled shack where one of the orphans, an unwed 14-year old girl with a baby, lived with her grand-parents and brother and sister. They encouraged me to take pictures and invited me to hold the baby. They kept telling me how horrible her circumstances were, pointing out the corner of the unlit hovel that was her bed. I didn't tell them that I spent several winters living in a dirt-floored hut one-third the size of this house in Mexico with a girl friend.

I had planned to put up my tent at a lakeside campgrounds, but George invited me to spend the night in his compound, where one of the orphans lived and was looked after by an amputee. In the courtyard were two goats tied up munching hay. George said they had just arrived and would be next Friday's luncheon.

I had yet to see Bukoba's Lake Victoria shoreline, about a half mile away. It was late in the afternoon, so I made a quick ride down to the lake and then rejoined George and Mbasa and Mr. Raza at the petrol station. Mr. Raza gave me a letter to deliver to an American nun who lived at a convent 20 miles south on my route the next day. We shared a glass of freshly squeezed sugar cane juice, then George and I walked back to his quarters where the caretaker prepared dinner for us. While we waited George gave me a photo show on his computer of the many people Mr. Raza had assisted, with close-ups of many of their horrific ailments.

His screen saver was a photo of Stonehenge. George didn't know what it was, he just liked the image. He thought it was a natural wonder and was shocked to learn that it had been created by pre-historic man. I explained that it served as a calendar. It was also news to George that at the extremes in the northern and southern hemispheres in the summer time it is daylight until midnight or later and that in the winter time it is dark for most of the day. On George's second lap top his screen saver was the rapper 50 Cents, but the music he chose to play was by Abba, a group he likes even more.

It was nearly ten o'clock when we were through with dinner. We took a stroll through the mostly quiet down town in search of an open store so George could buy some cigarettes. Rather than a pack, he bought four. George had a bunk in his room, but I chose to set up my tent on the concrete of the courtyard. The goats were put into a room for the night.

The next morning Mbasa came by to take me to the lakeside to see the fish market. George came along with his camera. I rode my bike while Mbasa rode on the back of a motorcycle and George on the back of a bicycle. There were clusters of bicyclists all over town offering rides on their rear racks. Short rides were 200 shillings, with 1300 to the dollar. Mbasa was well known among the fishermen. The day before when I asked a fisherman if I could take his picture he wanted 1000 shillings. Today no one made any such demands. Dots of islands lay off the shore, some large enough for people to live on. Mbasa bought a couple of the Nile Perch for his luncheon.

When we said our farewells I thanked them for their great hospitality and tremendous welcome to Tanzania. Mbasa assured me I would be treated well during my entire stay. Unlike many of its neighboring countries that have been riven by tribal rivalries that has resulted in great bloodshed, Tanzania has been most peaceable. "We Tanzanians like each other," Mbasa said.

Later, George

Bukoba, Tanzania

Friends: Unlike Uganda, where nearly everyone speaks at least a modicum of English, hardly anyone I've encountered so far in Tanzania speaks the mother-tongue, even though Tanzania too is a former British colony and most signs are in English. I'm 50 miles into the country and other than at the immigration office, I have met only one English-speaker so far, the 50-year old manager of a gas station here in Bukoba, as good-hearted a person as I've met in my travels.

As I paused in the heart of this good-sized, lakeside city, looking this way and that hoping to spot a restaurant, a tall, bald-headed gentleman wearing a white shirt asked if I needed help. This was no tout. His sincerity was unmistakable. I had a number of things I was looking for beside a meal--a bike shop, an Internet cafe, a bank, a grocery store. My new friend Mbasa said they were all nearby, but before searching them out, I had to eat, as I was starving.

I had camped in a small forest 25 miles back and hadn't had any food other than a couple of bananas and an energy bar. I stopped at the first two restaurants I saw as I entered Bukoba, desperate to get some food into me, but neither were serving yet. That's when I learned how scarce English-speakers are. In Uganda I could have easily coaxed some eggs from those cleaning and prepping the restaurant, but not here. Mbassa confirmed that few Tanzanians speak English.

After a hearty breakfast of eggs and chapati and orange juice we headed to the nearest bike shop, just a block away. I quickly learned that Mbasa seemed to know just about everyone in Bukoba despite its size as the second largest city on Tanzania's portion of Lake Victoria, longer than Uganda's and Kenya's combined. We had to go to half a dozen bike shops before we could find what I was looking for--a 700 by 28 tire. Surprisingly most had 27" tires, and a couple of the shops tried to sell me that. If I were desperate, I could have settled for a 700 by 35, a fairly common size for the heavy-duty bikes that predominant here.

Even though I'm not even 500 miles into these travels, I needed a tire as I had unknowingly scraped a small hole in the sidewall of my front tire and suffered a blow out on a steep descent when the rim overheated and the tube slightly bulged out through the rupture. I could hear a scraping sound moments before the explosion. I figured I'd picked up a thorn or a nail and began braking to extract it before the inevitable flat, but not soon enough.

If it had been a normal puncture through the tread that would have been easy to patch and not so calamitous. But a ruptured sidewall is a different matter. I could temporarily cover the hole in the sidewall with a dollar bill, but the tire was weakened and slightly bulging at not only that rupture but at another thin point in the sidewall. I managed 80 nervous miles since the flat to Bukoba, and hoped I didn't have to push my luck any further.

I was also in need of a couple of spokes. I broke a crossing pair on the non-freewheel side of my rear wheel, no doubt thanks to the pounding of those all too many fiendish speed bumps. I had brought three spare spokes, so was down to just one spare. When the spokes broke, I can't say. Early one afternoon I heard a clinking sound coming from the back of my bike. I stopped to investigate, assuming something had come loose. But no, it was a pair of broken spokes. I could have been riding in such a condition for any number of miles.

Other than having to tend to my bicycle's woes and the shortage of English-speakers, Tanzania has been treating me well. I was able to easily wild camp for the first time on this trip. Tanzania is nearly four times the size of Uganda, which is the size of Oregon, but has only 37 million people, six million more than Uganda. Immediately upon crossing the border I was greeted by patches of forest and wide open unsettled countryside. I could breath easy knowing that I wouldn't have to luck into a wild camp site, as I only manged to do twice in Uganda.

It was no fun though having to pay an unanticipated $100 in US currency for a visa at the border, twice what Lonely Planet said it would cost. Lonely Planet was also wrong about the location of the border post. It said it didn't come until the first town 30 kilometers into the country. When I stopped at the first immigration office I saw at the border I assumed it was the Ugandan office. But I had managed to cross into Tanzania without realizing it. It was actually Tanzania's immigration post.

The Tanzanian official went outside with me and pointed out the Ugandan office a couple hundred meters away. When he noticed where I had parked my bike, he cordially said, "When you return, could you park your bike somewhere else. Your bike is leaning against the national flag."

It was the quietest, most nonchalant border crossing I have ever experienced. I was the lone customer at both posts, small two-room cottages that were easy to miss. Nor was the border teeming with money changers. One offered his services, but I had already managed to change my money with the friend of a woman at a small grocery store where I had stopped for a final drink and loaf of bread on the Uganda side of the border. I had discovered the night before my few remaining slices had grown some mold, not surprising since they were several days old and no doubt preservative-free.

There was no shade outside the store, so I asked the woman if I could sit on a stool behind her counter. She was happy for the company. Like everyone I have encountered, she couldn't conceive of what I was doing. She asked me if I was doing research. I told her I was in a way, though not in any official capacity." She blurted out to each of her customers, "This man has bicycled all the way from Entebbe."

Bicycles are quite common, much more so than present day China, but only for short excursions. The vast majority of bicycles are Heroes from India. Few riders are strong enough to power these one-speed tanks up the hills. As I approach the longer, steeper climbs, I frequently see a string of people pushing bikes, some with loads of a hundred pounds or more of bananas or water or wood or passenger.

Mbasa has just come by and said the owner of the gas station would like to meet me.

Next up: goat and rice lunch with 60 HIV orphans, who I've been invited to give a lecture to on my travels.

Later, George

As I paused in the heart of this good-sized, lakeside city, looking this way and that hoping to spot a restaurant, a tall, bald-headed gentleman wearing a white shirt asked if I needed help. This was no tout. His sincerity was unmistakable. I had a number of things I was looking for beside a meal--a bike shop, an Internet cafe, a bank, a grocery store. My new friend Mbasa said they were all nearby, but before searching them out, I had to eat, as I was starving.

I had camped in a small forest 25 miles back and hadn't had any food other than a couple of bananas and an energy bar. I stopped at the first two restaurants I saw as I entered Bukoba, desperate to get some food into me, but neither were serving yet. That's when I learned how scarce English-speakers are. In Uganda I could have easily coaxed some eggs from those cleaning and prepping the restaurant, but not here. Mbassa confirmed that few Tanzanians speak English.