I rode segments of three stages today skirting the Alps while the peloton went into the thick of the high passes with three Category One and one Beyond Category climbs. I began the day riding a few miles off today’s stage after camping along Lake Annecy. I turned off and headed down valley, much of it on a bike path, to Albertville, twenty miles away, the start of the next day’s stage. The course markers had just been placed. After a couple of miles I turned off and proceeded for fifty miles of relative flat along the Isère River on the shoulder of the Alps to Grenoble, which the peloton will pass through on Friday’s thirteenth stage after starting in Bourg d’Osians on its way to Valence.

I arrived in Grenoble in plenty of time to find a bar and watch the final two hours of the day’s stage, the peloton’s first foray into the Alps. The bulk of an early twenty-one-rider break, including the Yellow Jersey, was just cresting the first of the day’s four major climbs. It had a seven-minute advantage on the peloton containing all the GC contenders. There were fifty miles of racing to go. Sky was setting the pace for the chasers, but not showing much concern. Since the stage ended with a nine-mile descent from the Col de la Colombière to the finish in Le Grand-Bornand none of the climbers wished to attack on the final climb and have to hold off the chasers to the finish. Froome and company were content to let the breakaway group battle for the stage win and save themselves for the next two stages when the finish is at a mountaintop and they can battle it out on the incline.

It turned out to be another great day for the French with Julian Alaphilippe claiming the first stage win for the home country and the climber’s jersey with it. He won by over a minute, allowing him to savor the final couple of miles. There was nothing going on behind him, so the camera could remain fixed on him for a full five minutes so all of the French could revel in his victory. He broke into a smile as happy as any on Sunday after the World Cup win. Van Avermaet could be happy too, not only keeping the Yellow Jersey, but extending his lead by a minute, meaning he might possibly be able to keep it for the stage after the next, though not likely if the climbers truly get serious tomorrow.

The after-effects of the cobbles weren’t as severe as some feared with only Uran of the prime contenders faltering, losing another 2:36 leaving him hopelessly out of the picture 7:08 down. Van Garderen is totally out of the conversation coming in eleven minutes down. Dan Martin and Bardet recovered nicely from their Sunday battering hanging with the contenders, Martin even leading them in.

If I had wanted to subject my legs to the day’s killer climbs I could have set out on them on the Rest Day, but instead I made a Rest Day of it myself, partially because there was an evening event in Talloires, three-fourths around the lake I wished to attend—a panel discussion of journalists whose podcast I religiously follow. I lingered in Annecy until noon, hanging out in the park the peloton will set out from and dropping in on the large, modern civic building overlooking the start. It was a hive of activity containing the library and tourist office and gallery and various shops and a large mall-like atrium with tables and chairs. It had a row of nine vinyl panels documenting the relationship between The Tour and the two World Wars. Fifty cyclists who rode in The Tour in its first years from 1903 to 1914 died in WWI, including 15 of the 145 starters of the 1914 Tour. Winners of The Tour who were killed in WWI each had a panel—Lucien Petit-Breton, Octavio Lapize and Francois Faber. A panel was also devoted to Robic, the winner of the first post-WWII Tour.

It was s fine display and good history lesson that attracted plenty of attention. It was fascinating to see how thorough and attentive people of all ages were, wanting to learn about The Tour’s past. But the yellow course markers I could see out the windows were too much of a lure to sit long and watch the parade of onlookers. But I couldn’t stick to the markers as long as I wanted as after less than a mile of bumper-to-bumper traffic driving along the lake, I abandoned the road and joined the steady stream of cyclists on the bike path between the road and the lake. When I reached the tip of the lake ten miles away I stopped for a picnic.

The traffic had thinned at that point and I could join the road as did other of the more serious cyclists. Riders were adorned in all manner of jerseys, many of Tour teams. As I ate I noticed four guys in matching uniforms of the Bora-Hansgrohe team. With them was someone wearing a white jersey. When they came closer I saw the stripes of the World Champion on the jersey. It was Sagan with four of his teammates out on a loosening-up ride after their flight from Roubaix the night before. Sagan has to wear the Green Jersey of the Points leader during The Race, so he was taking this opportunity to model his World Championship Jersey. He looks stunning in each.

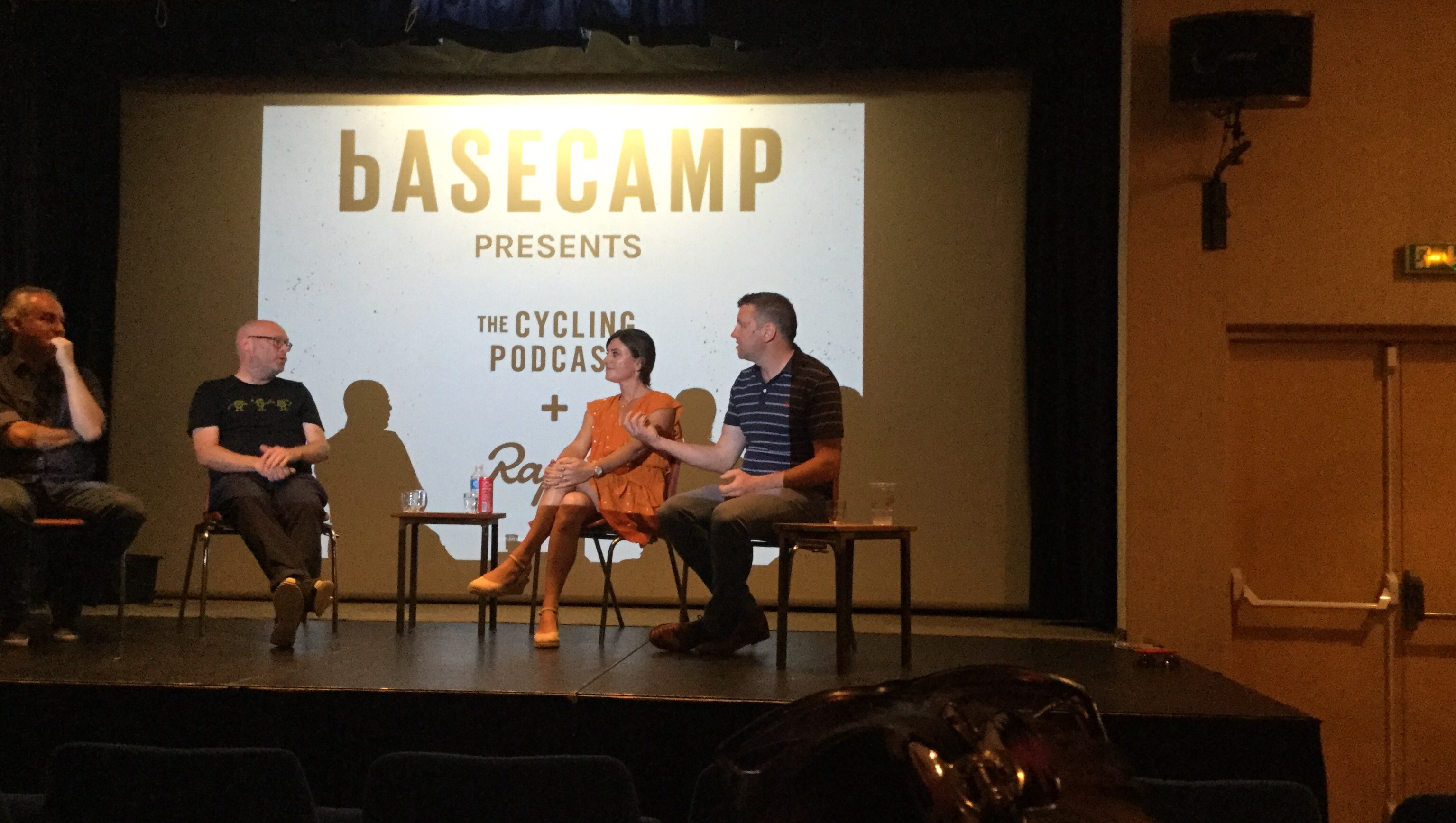

After my break I continued seven miles to the village of Talloires, up the only climb around the lake. I verified where the evening’s event was to be—in the town’s small cinema. It wasn’t for several hours so I found some shade in a park overlooking the lake and spent my wait eating some more and reading Balzac and trying not to be too excited about seeing in person journalists I had read for years and come to know through their first-rate podcast. I was among the first to take a seat. Before the journalists took to the stage, they stood to the side talking. I tried to guess who was who. The woman was obvious, Orla Chennaoui, and the shaggy French-looking guy had to be François Thomazeau. The bald guy was no doubt Lionel Birnie, which meant the tall, boyish-looking guy with short hair had to be Richard Moore, the one I was most hoping I could talk to afterwards as he had written the best book on cycling of the many I’ve read—“Slaying the Badger” on Greg LeMond’s triumph over Bernard Hinault in the 1986 Tour.

They were introduced by the sponsor of the event, the owner of a local high-end bike shop catering to tourists that also had a bar. He seemed English, though he pronounced Lionel in the French manner. Richard, on the right, apologized for the late start, as they’d had an eight-hour drive from Roubaix that took longer than expected. They were worried even about making the event. It was exciting to be watching as well as listening to the personable expertise of these familiar voices who I’d enjoyed for years. They have a great following, as evidenced by the crowd of mostly Brits that were here and happened to be following The Tour.

After twenty minutes they were joined by a couple of surprise guests, Jonathan Vaughters, former racer during the Lance era and founder of the Garmin team whose new sponsor was Education First, and his chief financial backer, Greg Ellis, a hedge manager. Vaughters is one of the exceptional minds in the sport, who comes from good stock, his father a lawyer and his mother an academic. He writes with great erudition, appearing in the New York Times on occasion, and is mentioned as a possible future head of the UCI, the organization that runs professional cycling. I was sorry I wasn’t wearing my Garmin jersey, as that would have gotten a reaction from him. I was wearing my blue argyle Garmin socks, a hand-me-down from Christian Vande Velde I only wear during The Tour. I was sitting with crossed legs with one ankle elevated above the seat in front of me, but not high enough to catch his eye.

Vaughters operates on a much smaller budget than most teams, especially Sky, but has won the Giro and Paris-Roubaix and was the surprise of last year’s Tour with Uran finishing second. He said he has to be innovative to compete with all the better-funded teams and pointed out that IBM used to have a five million dollar research and development budget compared to Apple’s $200,000, but now IBM is forgotten.

When the program was opened to questions I was armed and ready with more than a dozen, hoping I could get in at least one in this crowd of aficionados. Foremost among them was asking what they knew of the semi-mythical story of Rene Vietto having a toe that was bothering him during the 1947 Tour amputated and demanding that his chief domestique do the same thing. Supposedly, Vietto’s toe resides in a bottle of formaldehyde in a bar in Marseilles. I have gone in search of it and couldn’t find it. The story is only mentioned in a handful of the many histories I’ve read of The Tour, making me question its veracity. I had a perfect opening for the question as Thomazeau had commented in one of the trio’s daily Tour podcasts that Lionel had been suffering from a bad toe on this Tour and got relief from a phsysio on the Astana team.

Since I was sitting in the third row I was able to get in the second question. I began, “François mentioned in one of your early Tour podcasts that Lionel had a problem with his toe. That brought to mind the 1947 Tour.” When I explained about Vietto having his toe cut off, the audience began laughing thinking I was going to ask if Lionel had considered cutting his off. “No, no,” I interjected. “I’m not suggesting Lionel cut his own. I was just wondering about the validity of this story.”

Before anyone could reply Vaughters blurted out, “I’ve never heard that story.” That is part of my contention. If it were true, it would be a fundamental story of The Tour and oft-sited to illustrate the toughness and commitment of riders to stay in The Race, as Craddock is presently demonstrating. Vietto’s toe would be a holy relic enshrined in a place of prominence as is Robic’s Yellow Jersey from the 1947 Tour in the basilica of St. Anne’s-de-Aubrey.

Before anyone could reply Vaughters blurted out, “I’ve never heard that story.” That is part of my contention. If it were true, it would be a fundamental story of The Tour and oft-sited to illustrate the toughness and commitment of riders to stay in The Race, as Craddock is presently demonstrating. Vietto’s toe would be a holy relic enshrined in a place of prominence as is Robic’s Yellow Jersey from the 1947 Tour in the basilica of St. Anne’s-de-Aubrey.

I knew that Thomazeau would have an answer. He’s covered The Tour since 1986 and is a voice of authority on all matters concerning its present and past. He’ll preface a remark with a statement such as, “Christian Prudhomme (the director of The Tour) is a very good friend and he told me...”. His English is impeccable. When Birnie commented, “You can almost hear the waves of Lake Annecy lapping on the shore,” he asked, “Can a lake lap? I thought that was only oceans and seas.”

Regarding Vietto’s toe he said, “I know that story well. It’s pretty much an urban legend started by the guy who wrote Vietto’s biography who wanted to embellish his book. Vietto did have a problem with an ill-fitting shoe in that Tour, but there is no evidence he had a toe cut off, though I did once meet a guy in Marseille who had a collection of Vietto memorabilia, including his bike and some jerseys, who claimed to have his toe. But he couldn’t produce it.”

When Vaughters took the stage Moore jokingly asked, “Have you been listening to Lance’s podcasts,” knowing the two of them don’t get along and that Lance takes shots at him on occasion. Vaughters says he doesn’t have time. I was hoping they’d ask him about Lawson Craddock’s training program that Lance accused Vaughters of butchering, but they didn’t, nor was I able to get in another question with so many others in the audience with upraised hands. But when Vaughters left the stage I was able to catch him as he walked down the aisle out of the theater, and raised my leg to him saying, “I’m keeping your socks alive.”

“Wow, those are from our first team kit ten years ago,” he responded. I told him of my connection to Christian, but he was in a hurry chasing after Ellis, so I could not raise the issue of Craddock’s training regime. When I let Christian know that his old socks had brought pleasure to his former boss and financial-backer Doug Ellis, he emailed back saying he thought my heading of “Sox” referred to Ellis, as he is also a part-owner of them.

Though I was cut short by Vaughters’ rush I was able to have a good talk with Moore and Birnie afterwards in the small plaza outside the theater. First I asked if they were being polite not asking Vaughters about Lance’s comment on Craddock. They were behind on listening to his podcasts and had missed that one. When I told them Lance had referred to Vaughters as a “fucking bonehead” Birnie laughed and Moore gasped, but weren’t surprised.

Besides the LeMond book, Moore had also written an award-winning biography of his fellow Scot, Robert Millar, Great Britain’s premier Grand Tour rider, who rode during the LeMond-era, until Wiggins and Froome came along. Miller didn’t respond to any of Moore’s requests for an interview when he wrote the book, because he had gone underground amidst speculation that he had had a sex change. Miller finally admitted it last year, ten years after the book. I asked Moore if there was a chance of a conversation between he and Miller on one of their special Kilometer 0 podcasts on offbeat stories during The Tour. He said that wasn’t likely as they aren’t on speaking terms. It’s not that he was upset about the book, but rather a story about it in which he didn’t like the way Moore was quoted.

Then we talked about how much fun he had writing “Slaying the Badger” interviewing all the principals in the first Tour won by an American, the year after the last Tour won by a Frenchmen. His favorite was Andy Hampsten, who has become a good friend. We could have talked indefinitely, but night was coming on and I had some riding to do. When we parted he and Lionel said they would be looking for me as they drove the course in the days to come.

1 comment:

SAdly i also passed Peter in aCamper Van , as i got 2 punctures just before that Castle on the route , as he came out of his Hotel , for that #looseningUp ride . He would not stop soi could do a Photo with te #StayinAliveAt1_5 gillet !

Staying in Grenoble YHA , with a Guy that gave me a lift out of Montmellion after the Depart from Bourg St Maurice at about MidDay .

No doubt i will be in Bourg Oisans in the morning , so catching up with you in Bordeaux seems thhe solution ?

Post a Comment