Rio de Janeiro is experiencing an extreme heat wave with temperatures well over one hundred degrees, but I’m continuing to be blessed by pleasant temperatures in the 80 after crossing the Equator in Macapa and returning to the northern hemisphere where the days are lengthening.

I can thank the generally overcast skies and regular dousings of rain for keeping the temperatures moderate. In the rare instances when the sky clears and I’m subjected to the direct rays of the sun it’s like being hitting by a flame-thrower. There is usually one hard downpour a day and a light drizzle or two. There are also spells of a light mist such as greenhouses use to spray their plants. I don't mind the rain at all except at the end of the day if it comes too close to camping time.

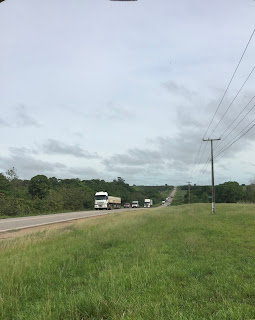

Contending with one hundred degree temperatures would not be pleasant in this lightly populated northern corner of Brasil with water and shade few and far between. There are stretches of sixty and eighty and another of over one hundred miles between towns in this final stretch to French Guyana. With so little traffic there are no extra service stations between towns and what service stations there are are so barebones they don’t have the tankards of ice water that I have come to take for granted.

It is most disheartening to no longer have them to look forward to. The restaurants don’t have the dispensers either, though some do have bottles of home-made ice water in their refrigerators they will share, though I can’t be greedy about it and have to be content with filling just one of my bottles. With so few people to cater to the restaurants do not have the buffets that fueled me up every afternoon. They at least all have trays of empanadas that provide energy enough.

I was expecting the junglish vegetation I experienced crossing the Amazon to continue, but it’s back to the savanna of thinly sprinkled trees. My day in the lush jungle aboard the ferry almost seems like a dream now that it is two days behind me. It was such a deep, unexpected immersion into the “backwoods” of the indigenous people I am still processing the amazing experience. I am almost wishing I had taken the return ferry and had another helping.

I can thank the generally overcast skies and regular dousings of rain for keeping the temperatures moderate. In the rare instances when the sky clears and I’m subjected to the direct rays of the sun it’s like being hitting by a flame-thrower. There is usually one hard downpour a day and a light drizzle or two. There are also spells of a light mist such as greenhouses use to spray their plants. I don't mind the rain at all except at the end of the day if it comes too close to camping time.

Contending with one hundred degree temperatures would not be pleasant in this lightly populated northern corner of Brasil with water and shade few and far between. There are stretches of sixty and eighty and another of over one hundred miles between towns in this final stretch to French Guyana. With so little traffic there are no extra service stations between towns and what service stations there are are so barebones they don’t have the tankards of ice water that I have come to take for granted.

It is most disheartening to no longer have them to look forward to. The restaurants don’t have the dispensers either, though some do have bottles of home-made ice water in their refrigerators they will share, though I can’t be greedy about it and have to be content with filling just one of my bottles. With so few people to cater to the restaurants do not have the buffets that fueled me up every afternoon. They at least all have trays of empanadas that provide energy enough.

I was expecting the junglish vegetation I experienced crossing the Amazon to continue, but it’s back to the savanna of thinly sprinkled trees. My day in the lush jungle aboard the ferry almost seems like a dream now that it is two days behind me. It was such a deep, unexpected immersion into the “backwoods” of the indigenous people I am still processing the amazing experience. I am almost wishing I had taken the return ferry and had another helping.

I could cross into French Guyana in two days if the road remains paved the final one hundred and fifty miles. I’ve heard conflicting reports on whether a sixty-mile stretch before the border has been paved. If it’s dirt and a heavy rain catches me on it, it could be rendered impassable on the bike. I’ll have to count on a benevolent trucker to get me through, as happened to me in Bolivia years ago.

The miles are passing so effortlessly for the first time, I am startled at times to discover I’ve gone fifteen or more miles and ought to be thinking of taking a rest. I am growing excited about crossing into French Guyana and being somewhat able to communicate with the locals. Since it is a French départment, I am hoping for the kilometer markers I’m so familiar with in France and whatever other cultural attachments to the home country it might have along with the euro as it’s currency.

It would be as exciting as ice cold water to find bottles of mint syrup for sale, so I can have my favorite drink, menthe á l’eau, through the three Guianas. That has me almost as excited as the Carnegie Library in Georgetown, now less than eight hundred miles away, that was the impetus for this trip.