For miles leading into New Orleans, even in the sparsely settled bayous dotted with houses on stilts, necklaces of beads littered the roadway. It was eight days to Fat Tuesday, or Mardi Gras, as is the French translation, and the culmination of all the parades and revelry leading to Ash Wednesday, when Lent commences and devotees begin a time of penitence and abstinence until Easter.

The necklaces were remnants of offerings from the many parades all over the city nearly every day for the past two weeks, sometimes as many as a dozen in a day in various parts of the city. Outside the city I wasn’t intersecting with parade routes, just spotting strings of beads discarded by those who had gathered them and had tired of them already.

They were mostly gold, purple and green, symbolizing the Christian trinity of power, justice and faith, though other colors slipped in as well. Once I reached the city proper any roadway could have hosted a parade. Necklaces were everywhere—in gutters, around people’s necks, dangling in trees, draped on fences, wrapped around tree trunks, adorning homes and plenty more scattered along the road.

I was fortunate to find accommodation at the packed 180-bed India House Hostel just off Canal Street. I was warned when I checked in that it was a party house, but most of the partying went on elsewhere and those in my 16-bed dorm when they trickled in, some as late as dawn, were respectfully quiet.

Janina and I had stayed at the hostel in January of 2014 when a polar vortex had many of the hostelers walking around wrapped in blankets. It was an ideal location, two blocks from one of the four remaining Carnegie Libraries in the city. It had been a yoga studio on that previous visit and remained so.

Six of the nine libraries Carnegie bequeathed Louisiana were in New Orleans. I had gotten to three of the four on that visit with Janina, but didn’t have the time to reach the fourth, as it was on the other side of the Mississippi that bisects the city, and necessitated using a ferry to reach it, as bikes aren’t allowed on the lone towering downtown bridge over the river.

Taking a ferry across the Mississippi was a fitting conclusion to these travels, as five weeks before I was aboard a ferry crossing the Amazon. What a contrast. That Amazon crossing took 24 hours, this six minutes, the blink of an eye, truly putting in perspective the magnitude of the Amazon. The Mississippi, as are all other rivers, is a mere trickle in comparison.

I felt as if I was withholding a monumental secret from everyone else on the ferry, most with beads around their necks and in a celebratory mood. They wouldn’t know how to react if they knew a fellow passenger had recently been on a ferry crossing the mightiest river of them all on the other side of the equator. I had been dropping jaws at the hostel whenever anyone asked me where I was biking from. “Uruguay” left most speechless.

My first time to New Orleans by bike I had also left people stunned and without words to react. That was January 1986 when I biked down for the Bears Super Bowl. It was fourteen degrees when I left Chicago with twelve days to bike 900 miles with just ten hours of light each day. With the winds from the north I arrived in plenty of time. The hardest part of the ride was having to stay in hotels the first three nights until I reached Kentucky and the temperature moderated enough time camp and snow no longer covered the ground.

It was a different time back then. No one called the police on me. Rather someone in Mississippi, who told me I’d cycled a long way to see “a Mississippi black boy run” (Walter Payton), reported me to a local television station after our chat. Less than an hour later a camera crew in a van pulled up beside me and interviewed me as I pedaled along. The next day people repeatedly told me they’d seen me on the news the night before. No one from the NFL got wind of my story, nor did I go around advertising it once I reached New Orleans, otherwise I might have been invited on to the field for the coin toss.

After my quick crossing of the Mississippi it was less than a mile to the Algiers branch library in a quiet residential neighborhood of small boutique homes. As throughout much of New Orleans, the homes had a distinct character and charm, something severely lacking throughout my time in South America. Residents here exhibited a genuine sense of pride in their place of residence. It was uplifting meandering about the city soaking it all in, and for a rare time I thought I had come upon a place I wouldn’t mind living, or at least lingering for a while.

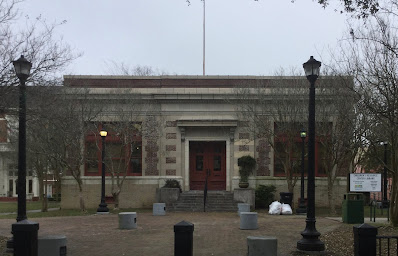

The Algiers branch still functioned as a library. It’s corner lot was flanked by park space to its left and right, that remained open rather than lost to expansion. A sign in the window above the bike rack offered bike locks to those without.

New Oreleans is so compact it took no time to return to the other two Carnegies on the other side of the river whose acquaintance I had made six years ago. Though I’ve been to hundreds since, I could clearly visualize them and their location. They’ve all left a strong, enduring impression.

The Dryad Branch, built to serve the “colored” community back in the era of segregation, stood regally at the end of Oretha C Haley Boulevard allowing those approaching it a prolonged look at all its majesty, causing one to wonder what this grand edifice might be if one didn’t know. It is now a branch of the YMCA.

When I flew off to Uruguay three months ago to ride up to the Carnegie in British Guiana I had no designs whatsoever on all these bonus Carnegies in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, nineteen in all. They felt like a reward for all the trials I endured in South America—the ants and mosquitoes and mechanical difficulties and unrelenting steep hills and three days on dirt and spells of heat.

I am ready for some down time. I have three months of the four cycling magazines I subscribe to awaiting me and a host of books to track down, including E. O. Wilson’s treatise on ants and “Fordlandia” about Henry Ford’s ill-fated attempt to establish a rubber factory in Amazonia.

Janina and I always take a spring trip of some sort. The sooner the better, as the road ever beckons.