Shortly after I began wandering around Georgetown’s Carnegie reveling in its majesty and actually being there, a young woman asked if I was George, as my long-time cycling compadre Tomas had alerted the library of my arrival. I certainly stood out, the lone white in the packed library of mostly children doing homework. There was hardly an empty chair for me to sit in if I had so desired.

Arriving so late in the day, I still had to find a hotel and possibly a bike shop to get the bike box hassle over with, so I had no time to sit and soak it all in. I wouldn’t have lasted long anyway, as the library was sweltering with no air conditioning, just fans circulating the hot, humid air.

It did have a room of computers for internet access, but not of the library’s holdings. It clung to the era of the card catalogue, possibly the last of the 2,509 Carnegies doing so. Miss Moore, as she introduced herself, and I traded photos of one another in front of it.

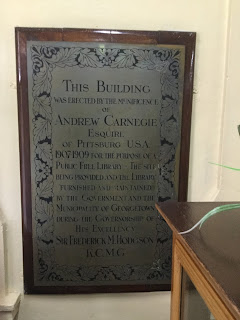

A plaque acknowledging Carnegie resides on the wall to the left of a grand stairway to the second floor that greets one upon entry to the library. As I ascended the stairs, my gaze was drawn to the high arched wooden ceiling.

When I took a walk around the outside of the library I came upon two bookmobiles servicing this city of 200,00, a quarter of the country’s population, that has only one branch library.

The library looks out at the Bank of Guyana from the corner of Main and Church Streets. A series of government buildings line Main Street that has a belt of green down it’s middle separating the traffic. A block away on Church is a towering Anglican Cathedral that someone on the ferry from Suriname told me was the tallest wooden building in the world. It was presently enclosed by a fence and undergoing restoration.

Miss Moore didn’t know the whereabouts of a bike shop, but the first cyclist I came upon directed me to Robb Street where there was a cluster of them. They’d all closed at five, so I’d have to wait until the morning when they opened at 7:30 in search of a box. I felt assured with so many to choose from that I could lay my box worries to rest and have a peaceful sleep.

It was just a mile from there to a hotel recommended by a cab driver. He said most hotels in town charged at least fifty dollars US, but this one should be about half that. I hadn’t spotted any budget hotels on my way to the library, so was happy to have this lead, which bore out. Unfortunately it had a weak fan that couldn’t disperse the no-see-‘ems so I erected my tent on the bed for the second time for my final sleep in South America.

I was forced into a hotel the night before too, as the road from the ferry for forty miles was lined with homes and businesses and it pretty much continued that way the final seventy-five miles to Georgetown. It was similar to the west coast of Taiwan down from Taipei and the east coast of Japan north of Tokyo, both totally built-up for over a hundred miles. At least it meant I didn’t have to worry about finding a cold drink in the ovenish heat. Oh how I longed for the plentiful ice cold water of Brasil.

Miss Moore didn’t know the whereabouts of a bike shop, but the first cyclist I came upon directed me to Robb Street where there was a cluster of them. They’d all closed at five, so I’d have to wait until the morning when they opened at 7:30 in search of a box. I felt assured with so many to choose from that I could lay my box worries to rest and have a peaceful sleep.

It was just a mile from there to a hotel recommended by a cab driver. He said most hotels in town charged at least fifty dollars US, but this one should be about half that. I hadn’t spotted any budget hotels on my way to the library, so was happy to have this lead, which bore out. Unfortunately it had a weak fan that couldn’t disperse the no-see-‘ems so I erected my tent on the bed for the second time for my final sleep in South America.

I was forced into a hotel the night before too, as the road from the ferry for forty miles was lined with homes and businesses and it pretty much continued that way the final seventy-five miles to Georgetown. It was similar to the west coast of Taiwan down from Taipei and the east coast of Japan north of Tokyo, both totally built-up for over a hundred miles. At least it meant I didn’t have to worry about finding a cold drink in the ovenish heat. Oh how I longed for the plentiful ice cold water of Brasil.

Every half mile was a sign sponsored by Pepsi of a new town, many British—Brighton, Liverpool, Manchester. There were so many some were simply numbered.

Guyana has been anticipating raising oceans for decades as the majority of homes are built on stilts, old and new. Each home had a distinctive quality.

I was struck by the range of personalities on the ferry. Several sought me out for a conversation. One told me the Guyanese have a strong entrepreneurial spirit and are fighters. I saw a number of help wanted signs—“worker wanted” in the vernacular and the not so politically correct “sales girl wanted.” The strong individualism was reflected in all these homes. The rustic were being taken over by the modern though. Gentrification of a sort.

Still there were many hold-outs.

The road was lined with flags of the two political parties with Election Day in a little more than a month. One resembled the red, black and gold Belgian flag. Some homes were unrestrained in identifying who they were supporting.

The incumbent party had fewer of its bland green and white flags, but made up for it with banners across the road of the president.

With the egg balls and the vibrant and energetic locals, I am sorry to be spending less time in Guyana than the previous four countries, though I do not regret at all escaping its oppressive heat. I was looking forward to the air-conditioned comfort of the airport terminal as I awaited my flight, but they don’t allow anyone into the terminal until check-in an hour before flights, subjecting me to an additional three hours of the heat. At least there is WiFi, and strong enough to download podcasts, unlike the previous two occasions I had access to WiFi in Guyana.

I would have had an even longer wait except I went to the wrong airport, not realizing there were two. It was lucky I was allowing so much time, partially to make sure I didn’t have to make any alterations to the bike box, as it was thirty miles to the new international airport, the longest I’ve had to ride with a bike box strapped to my back. I was nervous about the wind and the possibility of rain, but all turned out well. It was much less of a rest day than I anticipated, but allowed me to experience more of Guyana.

I’m happy to see I’ll be returning to seventy-degree temperatures in Florida. With excessive fees for my bike, $150 for each flight, I am opting for Amtrak for the final leg of my trip, picking up the City of New Orleans after I’ve gathered a few more Carnegies in Florida. Nine of the fourteen remain, though none in Miami. There is a cluster of five around Tampa that will be my next destination. Thanks to American Air Lines for making it possible.